The poet, painter and engraver William Blake (1757-1827), worked on the illustrations of his patron William Hayley’s Life of William Cowper (1803-4), and would have known through Hayley of Cowper’s voice-hearing experience – though Hayley’s Life obscures this, because it was understood at the time as discreditable. Later (c.1817) Blake recorded in marginalia to his copy of Johann Spurzheim’s Observations on Insanity his own voice-hearing experience of being addressed by Cowper on the ‘madness’ of the poetic imagination as seen from the point of view of Blake’s unholy trinity of extreme rationalists in science and philosophy:No voice divine the storm allayed,

No light propitious shone;

When, snatched from all effectual aid,

We perished, each alone:

But I beneath a rougher sea,

And whelmed in deeper gulfs than he.

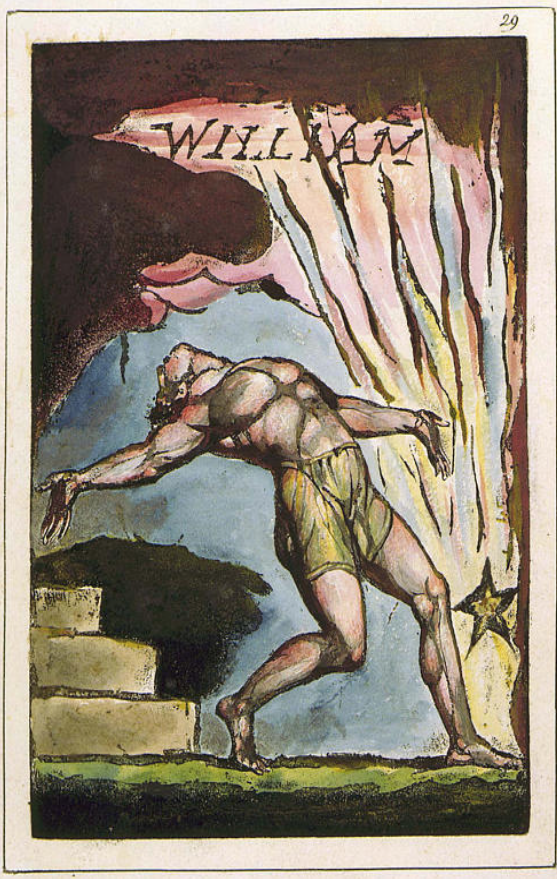

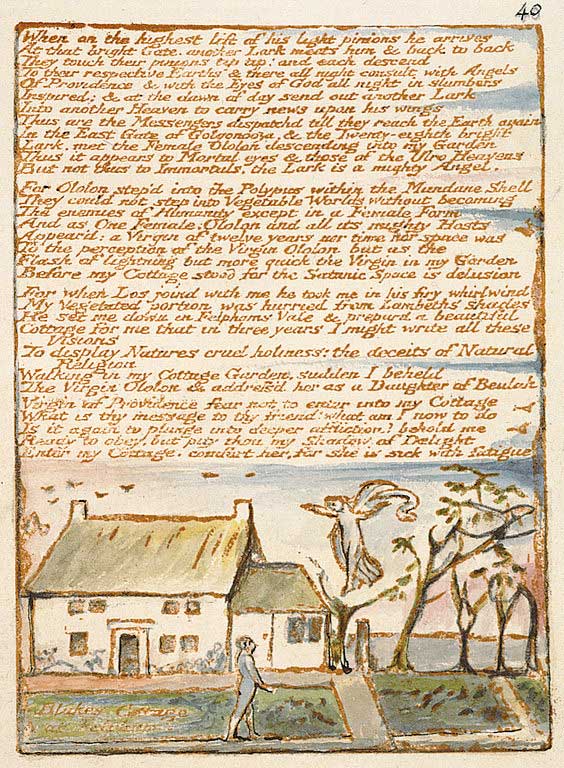

While his work frequently reports experiences of spiritual visitation which are visionary rather than auditory, Blake described himself on a number of occasions as writing his poetry from dictation by spirits (Letters of 25 April and 6 July 1803; Prelude to Europe [1794], Preface to Jerusalem [1820]). The exhibition, ‘Hearing Voices: Suffering, Inspiration and the Everyday’, contains his illustration of one of the most important voice-hearing experiences in the Bible, ‘The Lord Answering Job out of the Whirlwind’, from one of his last and most long-meditated visual works, the series of engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job (1826). Blake’s most developed account of voice hearing comes in his satire of the Swedish visionary, Emmanuel Swedenborg, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (c.1790).Cowper came to me and said, ‘O that I were insane always. I will never rest. Can you not make me truly insane? I will never rest till I am so. O that in the bosom of God I was hid. You retain health and yet are as mad as any of us all – over us all – mad as a refuge from unbelief – from Bacon, Newton and Locke.

The Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel dined with me, and I asked them how they dared so roundly to assert that God spake to them; and whether they did not think at the time that they would be misunderstood, and so be the cause of imposition.

Isaiah answered, ‘I saw no God, nor heard any in a finite organical perception; but my senses discovered the infinite in every thing, and as I was then persuaded, and remain confirmed, that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God, I cared not for consequences but wrote. Then I asked, ‘does a firm persuasion that a thing is so make it so?’ He replied, ‘All poets believe that it does, and in ages of imagination this firm persuasion removed mountains; but many are not capable of a firm persuasion of anything’.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plate 12, ‘A Memorable Fancy’.

Blake here teases the reader with a paradox. While he describes himself as literally speaking with Old Testament prophets he has the prophets themselves describe the voices they heard, and reported as the voice of God, as real perceptions but not literally voices. Voice hearing is reported, and a literal interpretation of what voice-hearing means is called into question.