Samuel Beckett

In 1935, acclaimed psychiatrist Carl Jung gave a series of lectures at the Tavistock Clinic in London. Amongst the audience was the novelist and playwright Samuel Beckett. In its preoccupation with voice – disconnected and disembodied – much of Beckett’s work seems to have been influenced by what he heard there. In the third lecture of the series, Jung said that “complexes” might:

emancipate themselves from conscious control to such an extent that they become visible and audible. They appear as visions, they speak in voices which are like voices of definite people.

Who is speaking, and to whom, is largely ambiguous in Beckett’s work. Pieces such as The Unnamable, Not I, and Company not only raise questions about speaker and listener, but also the more fundamental question of why speak at all? In these works, voices often wonder at their own need to speak, and the characters hearing them show distress as they realise the impossibility of stopping these constant, often tormenting, murmurs.

Not I

Disappointed by the first production of this piece, directed by Alan Schneider and played by Jessica Tandy, Beckett himself later directed Billie Whitelaw at the Royal Court theatre in London. His guiding principle was that the monologue should be incessant, delivered as quickly as possible, “at the speed of thought”.

Not I stages a voice battling with itself. The piece brings to the fore the hallucinatory nature of the everyday dialogue we conduct in inner speech by transforming it into a conflict of pronouns, desires, and perspectives.

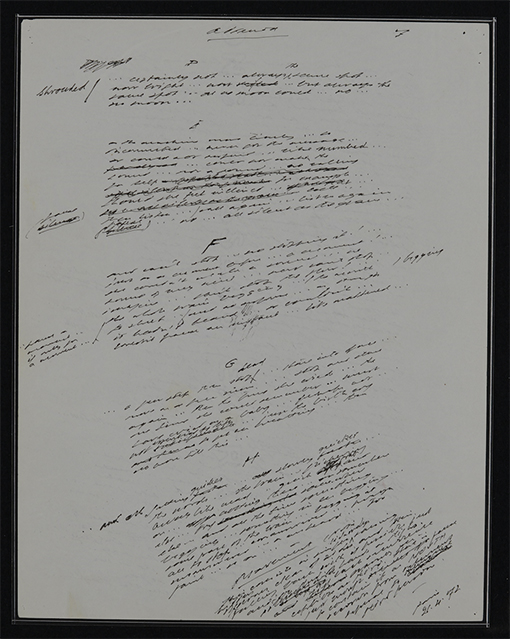

Samuel Beckett, holograph manuscript of Not I with handwritten alterations by the author, 1972

Samuel Beckett, typescript of Not I with handwritten alterations by the author, 1972

University of Reading, Beckett Archive – MS 1227/7/12/8 and MS 1227/7/12/1

Samuel Beckett and Billie Whitelaw in rehearsal at The Royal Court Theatre.

John Haynes/Lebrecht Music & Art

Company

An old man – ‘the one’ – lies alone in the dark. A voice speaks to him. Using the third person (“he”), the voice describes the one’s present. Using the second person (“you”), the voice narrates scenes from the one’s past. The first person is absent.

As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that the voice is inside the head of the old man, conjured by him as company to fill the dark.

More information

For more information about the representation of inner speech and voices in Beckett’s work, please see the following articles:

Marco Bernini, ‘Samuel Beckett’s articulation of unceasing inner speech‘, The Guardian, August 2014.

Marco Bernini, ‘Crawling Creating Creatures: On Beckett’s Liminal Minds’, European Journal of English Studies, 2015.