Suffering is part of many voice-hearers’ experience. Some people hear voices which are negative, violent, and abusive, and can be understood as a response to trauma, especially during childhood. Some people also suffer as a consequence of disclosing that they hear voices. It is not uncommon for people to feel disappointed or angered by their contact with mental health services, especially if they are forcibly medicated. Within the wider community, many voice-hearers also endure high levels of stigma, which can have a marked effect on self-esteem, quality of life, relationships, and opportunities.

Individual stories of and responses to suffering are important in developing and expanding knowledge and understanding of voice-hearing. Both positive and negative responses to these stories have profoundly changed attitudes to voice-hearing – cultural, social, legal, and medical. These have, in turn, had significant consequences for voice-hearers.

Daniel Paul Schreber was a distinguished jurist. In 1884, he was admitted to a clinic apparently suffering from psychiatric symptoms, and subsequently transferred to an asylum. Here, he wrote Memoirs of my Nervous Illness. Schreber was born in Leipzig in 1842, one of five children. His father, Moritz, wrote extensively on the subject of childrearing, particularly about instilling discipline through severe, coercive measures during early childhood.

Memoirs of my Nervous Illness is one of the most quoted, analysed, and interpreted psychiatric texts ever published. It was written not by a psychiatrist, but by a patient. The book offers vivid descriptions and analyses of Daniel Paul Schreber’s extraordinary experiences – miracles, persecution by little men, transformation into a woman. It was a key piece of evidence in Schreber’s legal appeal against his detention in the asylum and an assertion of his authority in interpreting what he underwent.

Sigmund Freud never met Schreber but used his Memoirs to develop his theory of paranoia. Schreber’s text was also analysed by Jacques Lacan in the later 20th century, and was pivotal in the development of psychoanalytic theories of psychosis. Alternative interpretations have focussed on Schreber’s father, and similarities between Daniel’s bodily “miracles” and the devices and methods used by Moritz. In light of this, Schreber’s experience has been seen as a response to childhood trauma.

Credit: Freud Museum London

On 18 August 1914, Eliza Bowes – an 18 year old girl from Houghton-le-Spring – was committed to the Winterton Hospital, Durham’s county asylum. On her admission, she was described as a “moderate grade imbecile” and noted to be noisy, restless, and continually crying. Eliza was hearing voices, which were calling her names. Eliza also had epileptic fits, which became more frequent over time. Eliza died at Winterton on 2 October 1915, from pneumonia.

Not all stories of suffering are told. Very little is known about the many voice-hearers whose distress has remained private, known only to themselves, families, and local communities, or contained within psychiatric institutions. The 20th century saw the rise of ‘talking therapies’ within mental health services. Prior to this, treatment tended to focus on subduing – even constraining and restraining – patients, and on silencing voices of all kinds.

Some voice-hearers have used creative and visual means to break that silence, to give expression to their experience, and to uncover stories that have been hidden.

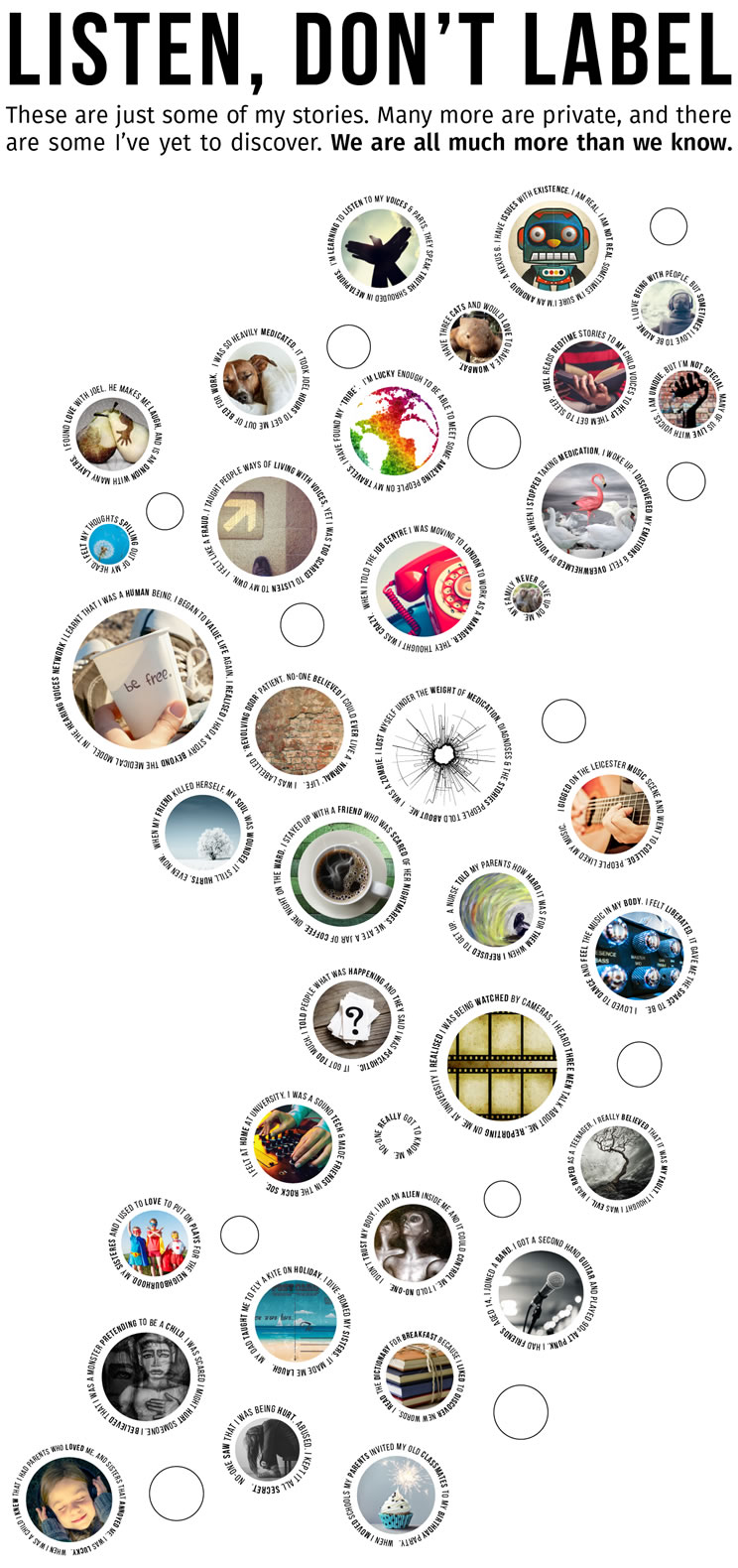

Rachel (Rai) Waddingham specialises in working with people who hear voices, see visions, have unusual beliefs, or are dealing with the impact of complex trauma. She is Chair of Intervoice – the international Hearing Voices Network, a trustee of the Hearing Voices Network in England, and Vice-Chair of ISPS UK. In 2009, Rai helped to set up the Voice Collective project at Mind in Camden, which supports children and young people who hear voices. A voice-hearer herself, Rai uses her own experiences as both a tool to help others and a reminder of what needs to change in our world.

Growing up, Rai lived in multiple worlds. In one, she was a gifted child with a family who loved her. In another, she was a monster, an alien, something dangerous. She kept this hidden world a secret, just as she hid the abuse. Although this abuse happened outside of her family, it cut deeply and left her with a deep sense of shame.

This shame shaped the experiences that were diagnosed as ‘schizophrenia’ when she was a young adult. Hounded by voices that reported on her every move, and feeling trapped in an alien conspiracy, her only recourse was to take high doses of medication as hope for recovery faded with each subsequent admission to hospital.

Rai found herself again, with the support of her family and the Hearing Voices Network. In a hearing voices group, she slowly began to make connections with others and to feel an ember of hope. She became curious about her experiences, seeking metaphorical, rather than literal, meanings. Rai now travels the world to help create alternatives for people in distress and is one of many voice-hearers advocating for change.

In ‘Get to Know Your Voices’, Rai focuses on creative ways to investigate the meaning behind voices. She writes:

For many, this may seem like a strange task. We can spend so long trying to block out the voices that we hear, especially if they talk about frightening or painful things, that the idea of exploring them may seem off-track. If you’d have spoken to me a decade ago I’d have said a similar thing. Still, finding ways of beginning to listen to (and think about) my voices has been an important step towards finding ways of living with them.

In ‘Becoming a Person’, Rai shares her experiences of being diagnosed with ‘schizophrenia’ and how she found her way back to feeling like a human being again. The video explores the relationship between childhood trauma, identity, ‘psychosis’ and recovery.