Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf began writing as a teenager. She drew from the events of her time, her own life, and her inner voices – some from memory but felt in the present and others from the world outside. Woolf’s writings embody how creative work emerges out of individual experience through reshaping memories and capturing inner and imagined voices.

Woolf often suffered ill health, both physical and mental. At the end, she found the distress too great to bear, especially after a number of bereavements and the loss of her London home in the Blitz. Before taking her own life, Woolf wrote to her husband Leonard:

I begin to hear voices and I can’t concentrate… You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read.

But this had not always been the case. Woolf had also enjoyed enormous creativity resulting from these episodes. They contributed not only to what she wrote, but also how through her version of ‘stream of consciousness’ that mingled the voices of characters and narrators. In 1930, she wrote to her friend, the composer Ethel Smyth:

As an experience, madness is terrific I can assure you, and not to be sniffed at; and in its lava I still find most of the things I write about. It shoots out of one everything shaped, final, not in mere driblets, as sanity does.

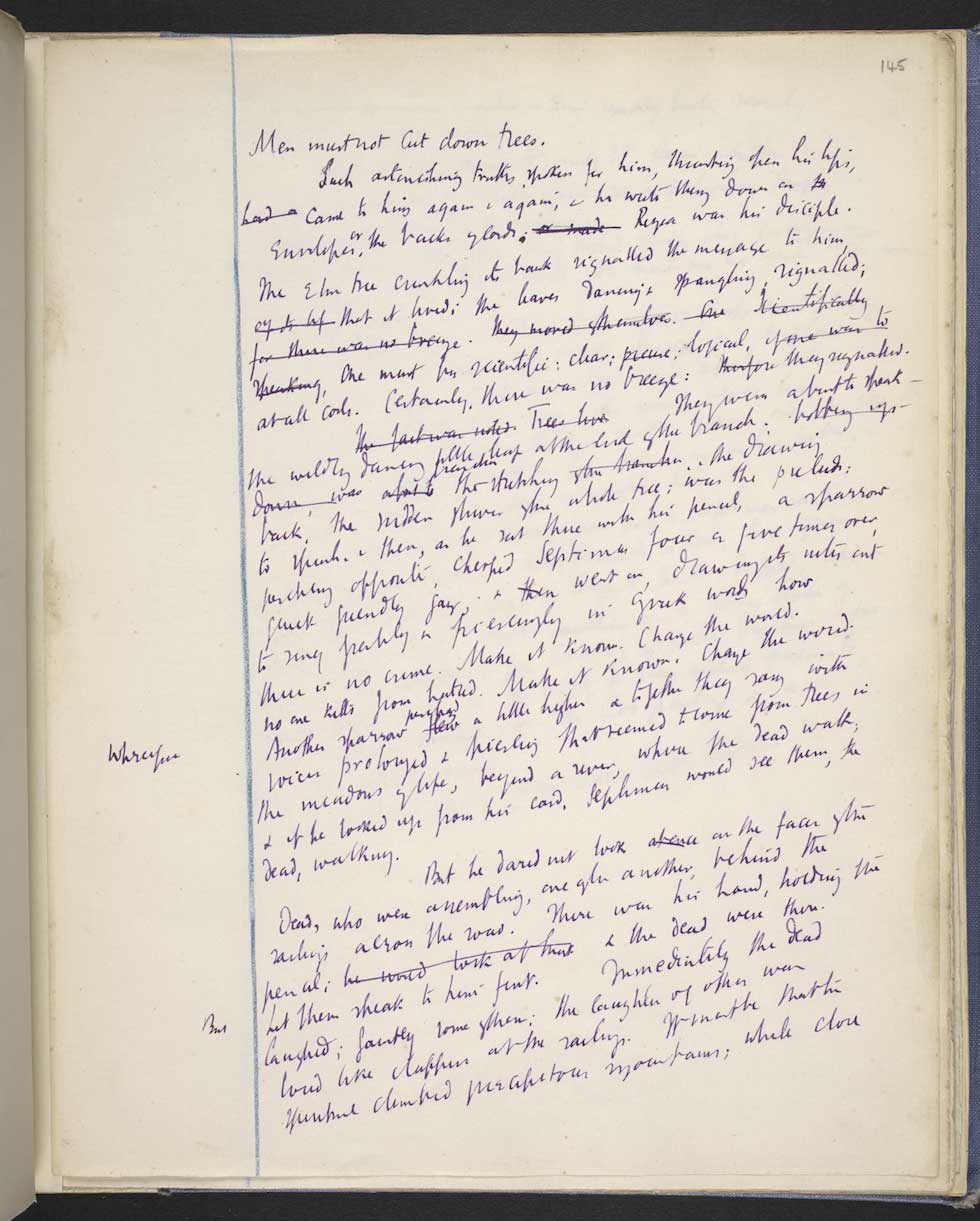

Mrs Dalloway, Virginia Woolf, f.145r

© The British Library Board, Add MS 51045

In Mrs Dalloway (1925), Woolf fictionalised the psychotic voice-hearing that she herself associated with early experiences of violation and loss: childhood sexual abuse, patriarchal bullying, early deaths of parents and siblings. But she displaces her experience onto the war veteran, Septimus Smith, and sets the novel in 1922, the year of the publication of the British Government’s first official report on “shell shock”. Septimus’s inability to communicate his memories and felt horror is compounded by the “violators of the soul”, his term for his doctors, with their reductionist preoccupation with eating and rest for exhausted “nerves”, their refusal to listen to his “message”. The doctors don’t listen to what the voices are trying to communicate, so Septimus kills himself. Woolf’s own suicide in 1941 occurred when, convinced she could no longer write and therefore “communicate” her own message, she left a suicide note to her sister intimating that the voices had returned but, because no longer communicable, no longer within her control.’

Patricia Waugh, ‘The Novelist as Voice-hearer’

To the Lighthouse, 1932

This semi-autobiographical novel presents two days in the life of the Ramsay family, interspersed by a period of around ten years. Woolf described writing this book as a form of therapy:

I wrote the book very quickly; and when it was written I ceased to be obsessed with my mother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not see her. I suppose I did for myself what psycho-analysts do for their patients. I expressed some very long and deeply felt emotion. And in expressing it I explained it and then laid it to rest.

Image: Vanessa Bell’s cover design for To the Lighthouse © The Victoria and Albert Museum, London

More information

Further information about the role of voice and voice-hearing in Virginia Woolf’s work can be found in the following articles, which are available to read freely:

Patricia Waugh, ‘The Novelist as Voice-hearer’, The Lancet, 2015.

Patricia Waugh, ‘Hilary Mantel and Virginia Woolf on the sounds in writers’ minds‘, The Guardian, August 2015.

Patricia Waugh, ‘It’s important to listen to imaginary voices – just ask Virginia Woolf‘, The Conversation, 24 January 2017.